The Search for Useful Proteins: Berkeley Startup Aims To Turn Generative AI Into a Gene-Fixing Tool

From Ron Leuty’s story in the San Francisco Business Times.

AI-powered Profluent Bio released the world’s first open-source, AI-generated gene editor, the Berkeley company said Monday, an effort that could help more scientists develop CRISPR medicines to fix a range of diseases.

Profluent, a roughly 20-person company launched by former Salesforce researcher Ali Madani and University of Washington assistant professor Alexander Meeske, said its OpenCRISPR-1 gene editor uses a protein, which it developed with large language models, and guide RNA that shuttles a cutting protein where it needs to go.

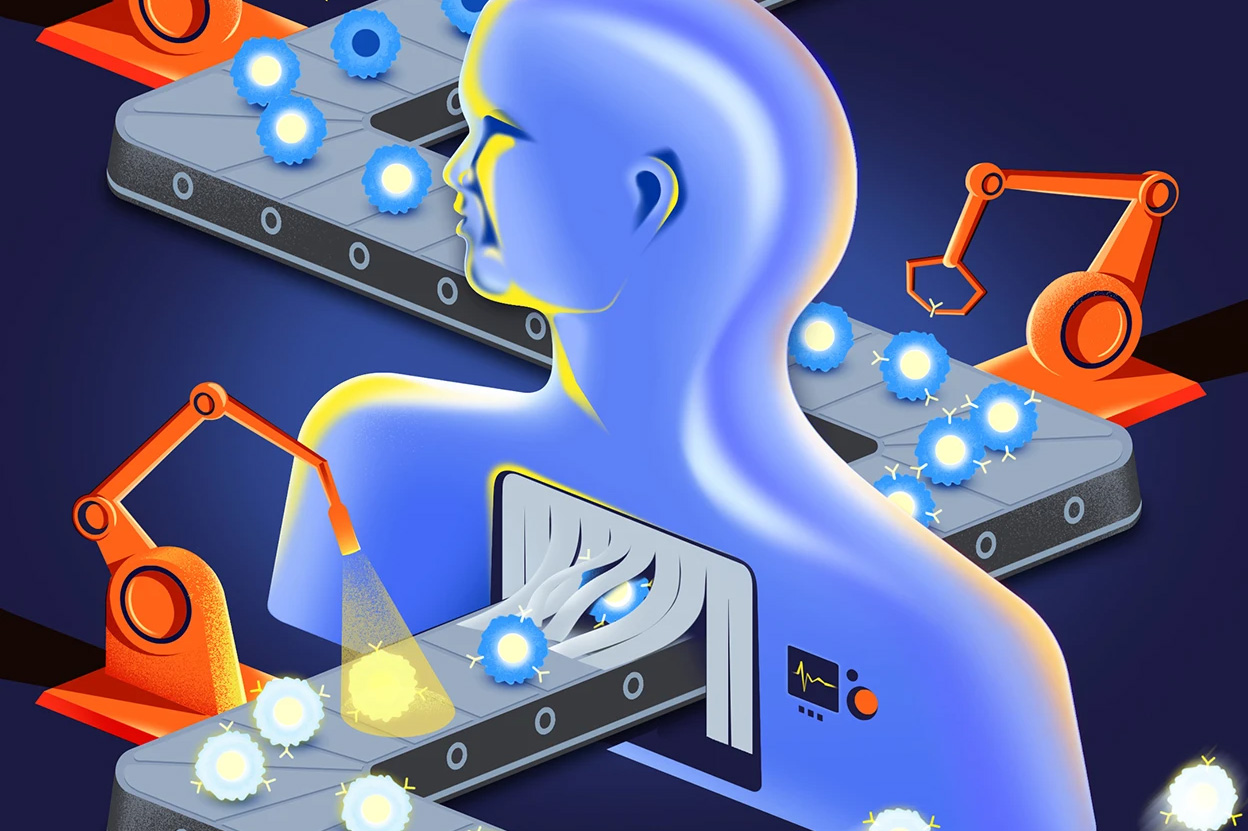

Proteins, which handle most of the work in cells, are central to human health and disease. If the bent and folded strings of letters that make up proteins — a sequence of amino acids — are off by one, that may be enough to throw off the cellular assembly line. That’s when diseases can occur.

Drugmakers have tapped protein-based drugs to treat heart disease and more. A number of Bay Area companies are working on protein degraders or stabilizers, depending what in the protein-making process has opened the door for a disease.

But proteins also can be cutting tools, for example, in the CRISPR genome-editing technology that brought University of California, Berkeley, chemist Jennifer Doudna a share of the 2020 Nobel Prize.

The search for useful proteins — whether for drugs or as cutting tools — has relied on finding a protein needle in nature’s haystack. Profluent, housed at the Bakar Labs incubator at UC Berkeley, is tapping artificial intelligence — specifically large language models, or LLMs, that are trained to analyze and generate language — to come up with new ways to find proteins.

In the case of Profluent’s OpenCRISPR initiative, its gene editor includes a Cas9-like protein, similar to the protein cutting tool in Doudna’s work. By releasing an open-source version, Profluent leaders hope more researchers build new gene-editing systems to fix mutations from in a range of diseases.

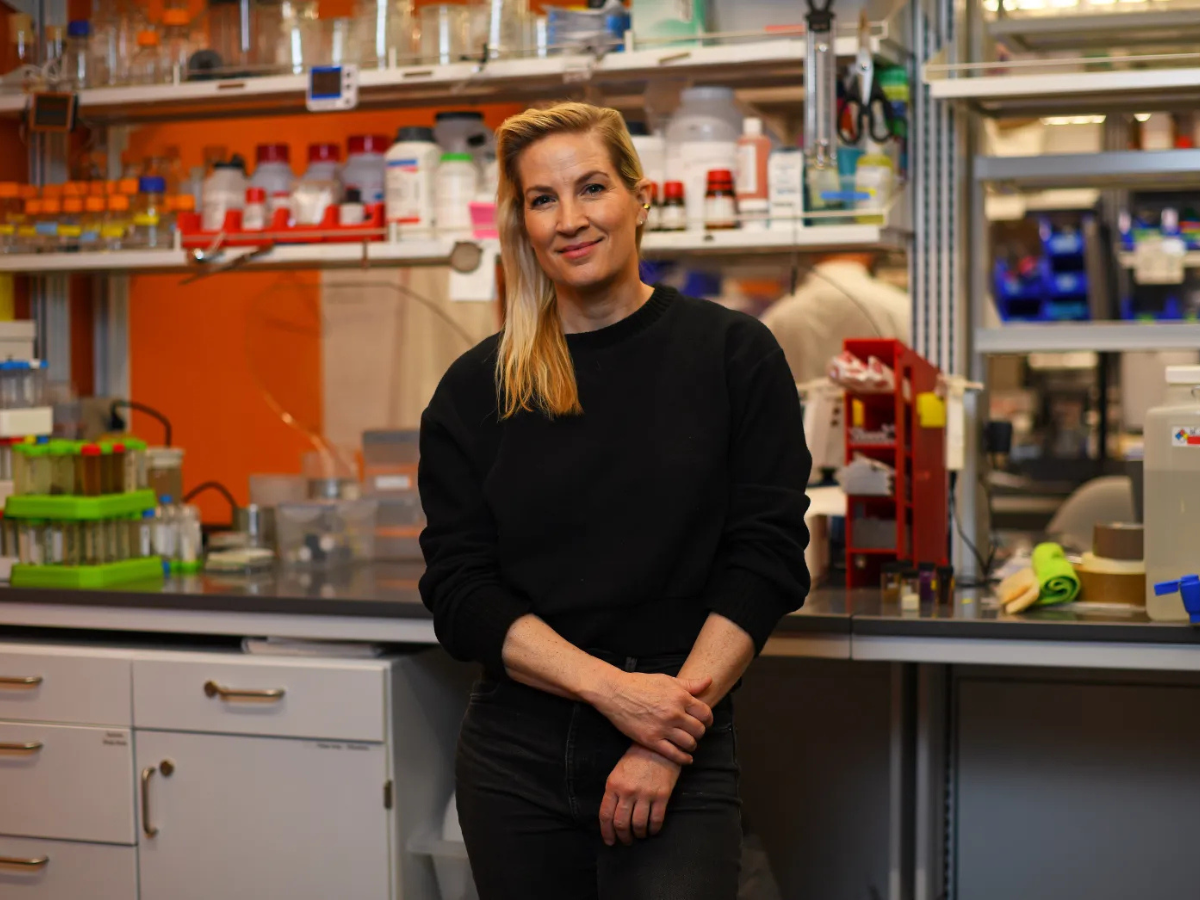

Profluent was borne out of AI brainstorming work started five years ago at Salesforce Research, where Madani led machine learning. One project zeroed in on protein design.

“It’s complex and difficult in the space because there are so many options,” Madani said.

The project enticed Madani to take time off from Salesforce, the customer relationship management software developer and San Francisco’s largest tech employer (NYSE: CRM), and ask people in the biotech industry if AI-generation of proteins not seen before in nature could be useful for them. Eventually, the work was outlined in a January 2023 Nature Biotechnology paper that also served as Profluent’s corporate introduction.

The company’s been moving quickly ever since. It now is seeking partnerships with drug developers, Madani said, but eventually plans to develop its own drugs.

While AI has been seen mainly as a tool for drug discovery or a bolt-on addition to aid existing discovery and development work, a new wave of AI-in-biotech startups seeks to use the same technology tapped for ChatGPT to discover targets for drugs. Rather than hunting for protein sequences found in nature then pasting them together or engineering them, Profluent, for one, is tapping AI to write sequences from scratch, specifically those not yet found in nature.

“You are no longer constrained by what you find in nature,” Madani said.

Profluent in February brought on Hilary Eaton as chief business officer to assemble partnerships. She previously was head of business development at Tome Biosciences and Vor Biopharma.

The company last month said it raised $35 million in a round led by Spark Capital. Also part of the capital infusion were existing investors Insight Partners and Air Street Capital, a syndicate of angel investors with connections to OpenAI, Salesforce, Octant Bio and Google, including Jeff Dean, the chief scientist of Google DeepMind.

It previously raised a $9 million seed round, it said in August.