Startup ResVita Bio Targets Rare, Deadly Skin Disease With a Bacterial Factory

Story by Ron Leuty at the San Francisco Business Times.

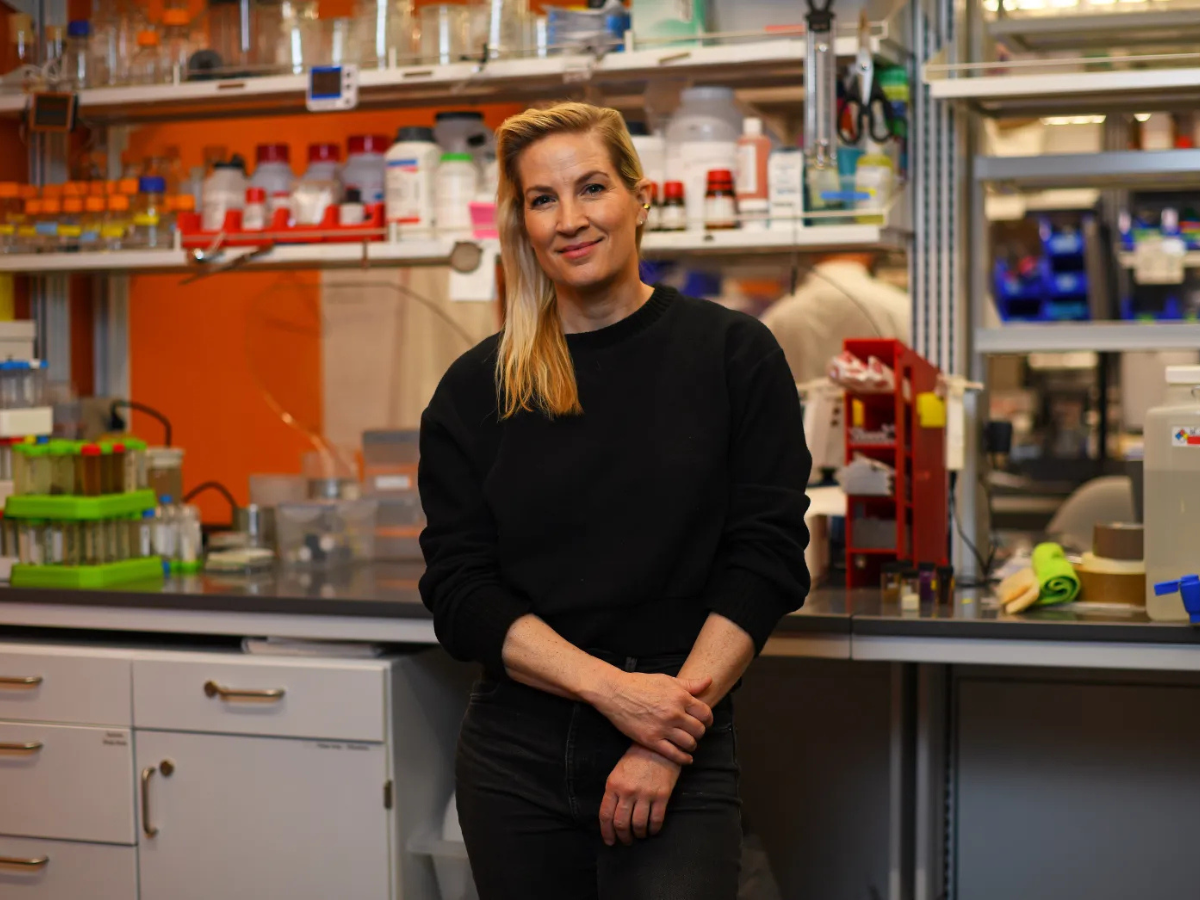

Amin Zargar literally put skin in his scientific game. Now he hopes to add a deeper layer of funding to his East Bay startup to boost its work on a treatment for a rare and deadly skin disease.

Zargar as a postdoctoral fellow was on an academic track and looking for a job as he stress-tested an idea kicked around with mentor Jay Keasling, a pioneer in synthetic biology at UC Berkeley. What if, they thought, they could genetically engineer a bacteria to convert sugars in skin lotions into therapeutic proteins continuously pumped onto the skin’s surface?

In essence, the bacteria would become a 24/7 factory for producing healing proteins.

If such a therapy could be developed, dermatologists told Zargar, an ideal early target would be Netherton syndrome, a rare, inherited skin disorder that forms intensely painful, dry and scaly patches.

The condition, Zargar said, is akin to missing the outer layer of skin and can be deadly to newborns. Some 20% of Netherton syndrome babies die within the first year.

For patients who survive, Netherton syndrome, which is thought to occur in one in every 200,000 births, becomes less severe. But treating the red and itchy patches remains a lifelong challenge — while most patients use moisturizers to attempt to soothe the condition, others resort to corticosteroids, which can be dangerous when taken over extended periods, or bleach baths.

After the Covid-19 pandemic kept him out of the lab, Zargar returned on a mission. Meanwhile, he was offered a faculty position in Denmark.

So as Zargar in November 2020 used a pipette to apply one of his lotions onto a square of skin on each arm, he thought to himself: If the bacteria stay alive and active for eight hours, he’d stay in the Bay Area and start a company; if not, he’d take the academic job.

Spoiler alert: The bacteria survived. In another lotion formulation, however, the bacteria later died.

“It was very close to me being in Denmark,” Zargar said.

Now his company — ResVita Bio, a tenant of the Bakar Labs incubator at the Berkeley BioEnginuity Hub — hopes to land a Series A funding round early next year. That money will take the company, Zargar said, into a clinical trial in 2026.

To date, the company has raised about $4 million, including more than $2 million from a Small Business Innovation Research grant from the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases.

Humans’ largest organ is skin-deep with potential treatments. From atopic dermatitis — the chronic inflammatory skin condition also known as eczema — to psoriasis’ red, scaly plaques, the skin has been a high-profile target for drug developers, averaging 46 new drugs per year between 2014 and 2023.

Broadly across the skin, Sonoma Biotherapeutics Inc. of South San Francisco in October launched an early-stage clinical trial with a drug aimed at a chronic inflammatory skin condition known as hidradenitis suppurative, while UCSF and the Belgium-based drug company UCB S.A. this month disclosed a partnership focused on finding treatments for hidradenitis suppurative, which disproportionately affects women and people of color.

Meanwhile, Stanford University researchers, led by bioengineering professor Michael Fischbach and postdoctoral scholar Djenet Bousbaine, recently described in the journal Nature how they domesticated a common skin bacterium, carrying a key protecting protein, that could be made into a vaccine spread on the skin.

In Netherton syndrome alone, Connecticut-based Azitra Inc. (NYSE American: AZTR) plans to have data in the first quarter from an early-stage clinical trial of its Netherton drug, and a lotion from Quoin Pharmaceuticals Ltd. (Nasdaq: QNRX) was cleared last week by the Food and Drug Administration to start a new Netherton study.

But Zargar said ResVita’s obsession with Netherton syndrome allows it to stand out. For example, there are no FDA-approved therapies for Netherton, he said, and the rare disease offers a good proof of concept that could mean the protein-producing bacterial factory idea could be used for other skin disorders.

What’s more, the continuous protein therapy mitigates proteins’ generally short lifespans, he said, and the bacteria are active only on the skin.

“You don’t have the systemic toxicity,” Zargar said. “The (lifespan of the proteins) isn’t long enough to go into the reproductive and respiratory system.”

ResVita has a rare pediatric disease designation from the FDA, though that program sunset Dec. 20, a victim of Congress’ budget-continuance bill. It also plans to apply for “orphan” and “breakthrough therapy” designations, which give financial benefits and speed the FDA review process for drugs to treat rare or serious conditions.

It’s a scenario Zargar said should resonate with venture capital firms, even as the life sciences industry deals with a three-plus year funding drought on Wall Street and Sand Hill Road.

“That’s kind of the ideal Series A value proposition at the moment,” he said. “People are reticent to fund things preclinically unless there’s a big value-inflection point.”