Jenny Hamilton, CEO of Stealth Startup, Featured in Story of Jennifer Doudna’s Women in Enterprising Science Incubator

By Ron Leuty at the San Francisco Business Times.

The future of women in life sciences is taking shape on the edge of UC Berkeley’s campus.

With its second cohort of young women scientists testing their problem-solving skills and entrepreneurial ambitions, the HS Chau Women in Enterprising Science Program within Nobel laureate Jennifer Doudna’s Innovative Genomics Institute is giving rise to a new generation of biotech startups. At the same time, the program is solidifying Doudna’s legacy.

Doudna, the 2020 Nobel Prize winner in chemistry for her role in developing the CRISPR genome-editing technology, is known as a mentor for postdoctoral researchers in her University of California, Berkeley, lab. She also has a penchant for guiding young scientists toward spinning out their work into new companies, such as Caribou Biosciences, Mammoth Biosciences and Scribe Therapeutics.

Count among them Jenny Hamilton, who was in the first cohort of four fellows to join WIES, as the program backed by Horizon Ventures co-founder Solina H.S. Chau is known. Hamilton did her Ph.D. in virology and heard Doudna speak at Mount Sinai Health Center in New York City.

One liberating takeaway from that event, Hamilton said, was hearing Doudna’s response to her career plan.

“I didn’t have a plan,” Hamilton recalled Doudna saying. “I just knew I would be able to figure it out. I’d go do one thing and if it didn’t work, I would go do something else.”

Hamilton, assuming she would start an academic lab, ultimately reached out to Doudna — “kind of fangirl a little bit, right?”

“I said, ‘I do viral engineering. I think the most useful way I could apply my background is toward trying to figure out new ways to deliver genome-editing tools and leveraging how viruses get molecular cargo from the outside of the cell to the inside of the cell.’ And she was like, ‘Great!’ and I came, interviewed and ended up joining her lab.”

That was 2018, and by being part of the biotech ecosystem around Doudna’s Innovative Genomics Institute, Hamilton then discovered the WIES program.

WIES is set up in the institute’s home, a 112,800-square-foot structure originally built for the Energy Biosciences Institute with money that was part of a controversial collaboration valued at $500 million with energy giant BP. Some academics worried that the BP deal would compromise the purity of academic research.

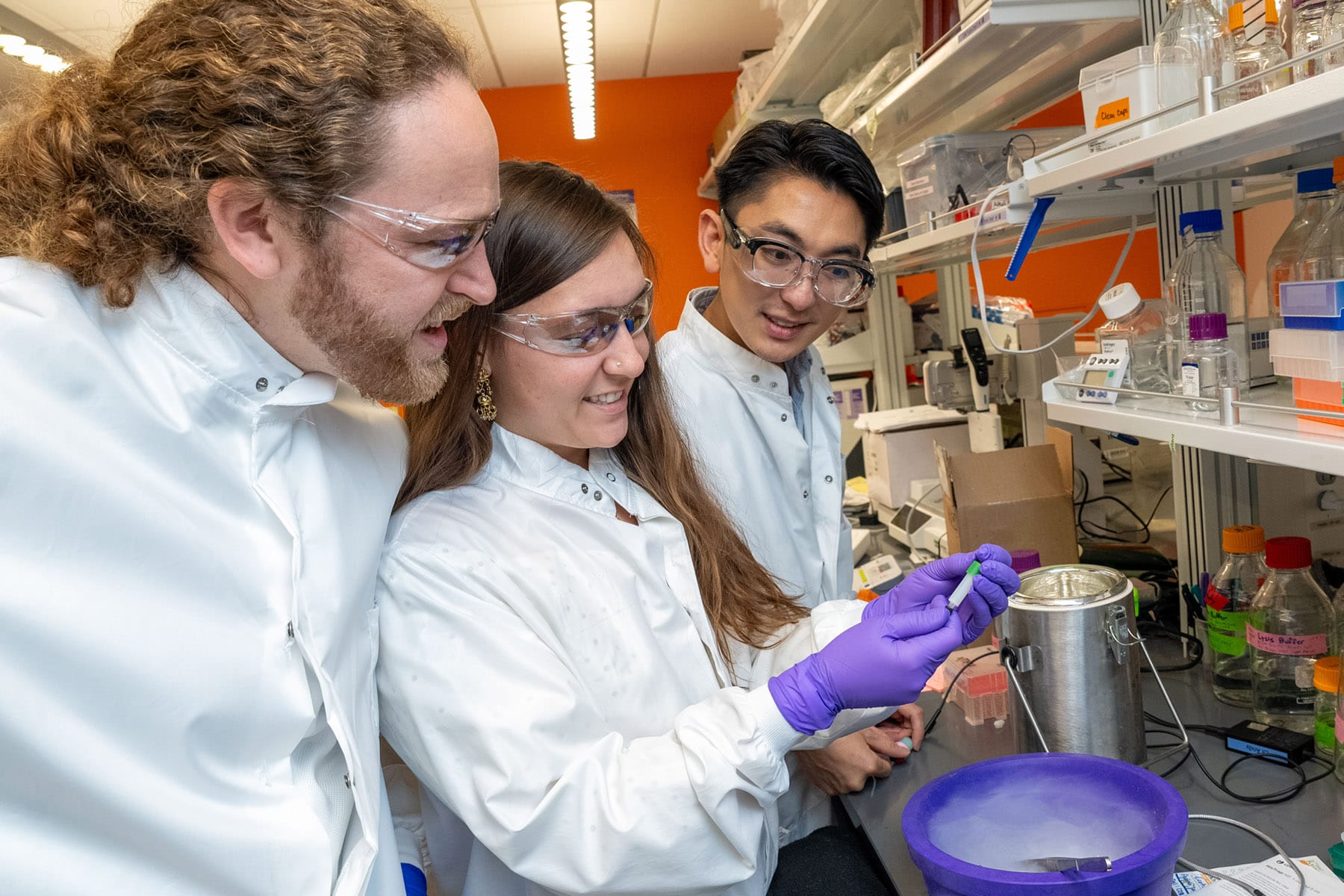

The Energy Biosciences Institute eventually moved a short distance away, but now from the 16-bench, first-floor laboratory, WIES fellows hatch plans to start new companies or push forward with more academic research. Upstairs is office space and a conference room.

“Berkeley has become such an entrepreneurial resource,” said Susan Abrahamson, the director of intellectual property at the Innovative Genomics Institute who is the director of the WIES program and part of its selection committee. “There are so many resources on campus, so it’s not like we have to reinvent the wheel for our program.”

WIES leaders pick four fellows from applications filed by postdoctoral fellows or faculty, including those at UC Berkeley, UCSF, UC Davis or UC Santa Cruz. The fellows’ 12-month appointments include up to $150,000 for salaries, benefits, programming and supplies in pursuit of projects ranging from an examination of the role of garbage-collecting white blood cells, or macrophages, in the immune system’s response to cancer to a nonediting way of tapping natural mechanisms of gene regulation to restore normal gene expression.

Ultimately, up to two fellows in each cohort are handpicked by Chau, who also is the director of the UC Berkeley benefactor, the Li Ka Shing Foundation, for a $1 million, no-strings-attached grant.

Hamilton’s project expanded on her research on viral-like particles to explore how CRISPR therapies can be safely delivered to specific cells. Still, she didn’t know if she wanted to pursue academic research or to commercialize her work.

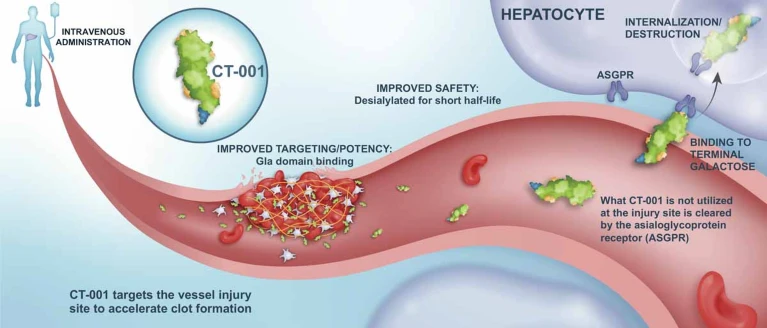

Her project, however, received one of the $1 million grants at the end of the one-year fellowship, and she and Doudna last summer founded a stealth-mode company trying to precisely deliver genome editors. It is housed in the Bakar Labs incubator at the Baker Bioenginuity Hub on the other side of the Berkeley campus.

Kelsey Hern, on the other hand, knew she didn’t want to follow an academic path and entered WIES this fall with a focus on starting a company.

That focus comes from her own health challenges. Hern in her early teen years battled an intestinal infection called Clostridioides difficile, or C. diff. Science now knows the bacterium is resistant to antibiotics, but it sent Hern on a quest to learn everything she could about microbial infections.

“It’s that thing all microbiologists have to have, that thing where they go: ‘This is so disgusting — and I’m so interested in that!’” Hern said.

In Sangeeta Bhatia’s lab at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Hern worked on breath-based diagnostics for respiratory infections. Then as a Ph.D. student she joined the lab of UC Berkeley synthetic and systems biology-focused professor Adam Arkin, focused on finding microbes in the lung that could be inhaled as probiotics to halt respiratory infections.

She applied for the program while finishing her Ph.D. and is a current member of the WIES cohort that started in September.

“I always thought in the back of my head, ‘Oh, wouldn’t it be amazing if I could — myself — be the person who starts a company?’ But I didn’t,” Hern said. “I guess that’s kind of the experience of women, where you say to yourself, ‘Oh, that’s not going to happen for me,’ or ‘I’m not the person. That’s not the face of the person who does that. Someone else does that.’

“So I think seeing the first cohort go through and seeing that actually there are faces of these companies who are women, too — I think that kind of gave me the idea that maybe it wasn’t off-limits for me.”

Included in the program are meetings with mentors and “near-peers” — people who may have experienced only a couple years ago what fellows face today. One of the current cohort’s near-peers, for example, is Hamilton.

“The struggle I always saw with speaker events is, if you have 30 people in a room, it’s hard to get the questions you want (answered), and then there’s that level of intimidation where you’re afraid you’re going to ask kind of a dumb question,” said Drew Yashar, an associate with Alix Ventures and adviser to the Innovative Genomics Institute. “I tried to pass along the message: dumb questions only.”

Soft skills about operating a science business evolve from those more-intimate roundtable sessions, Yashar said.

“I always thought people who create startups are lucky people,” Hern said. “Not anyone can do that. You have to be in the right position at the right time, but I just figured, I’ll throw my name in the pot and see.

“And I think the reality about this program is, you don’t have to be lucky. The program makes you lucky,” Hern said. “It puts you in the right position at the right time.”