How Berkeley Is Leaning in to the Biotech Boom

From the article by Elizabeth Moss in the San Francisco Business Times

When Joshua Yang and Daniel Estandian founded Glyphic Biotechnologies, a protein sequencing company, they hadn’t even met.

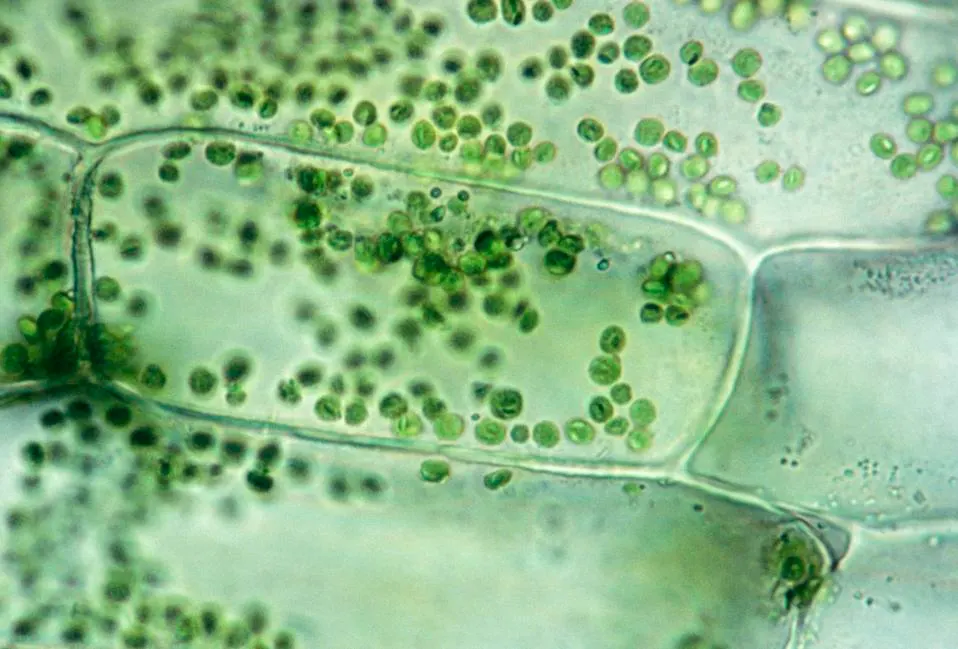

The two connected online last year while working at Nucleate Bio, a bioscience incubator headquartered in Boston that went virtual during the pandemic. Using a molecule called ClickP that Estandian developed as a Ph.D. student at MIT, they began developing a device that would sequence proteins at a much larger scale than currently available on the market. From their respective homes on opposite sides of the country, they managed to raise $6 million dollars in venture capital funding without ever meeting face to face.

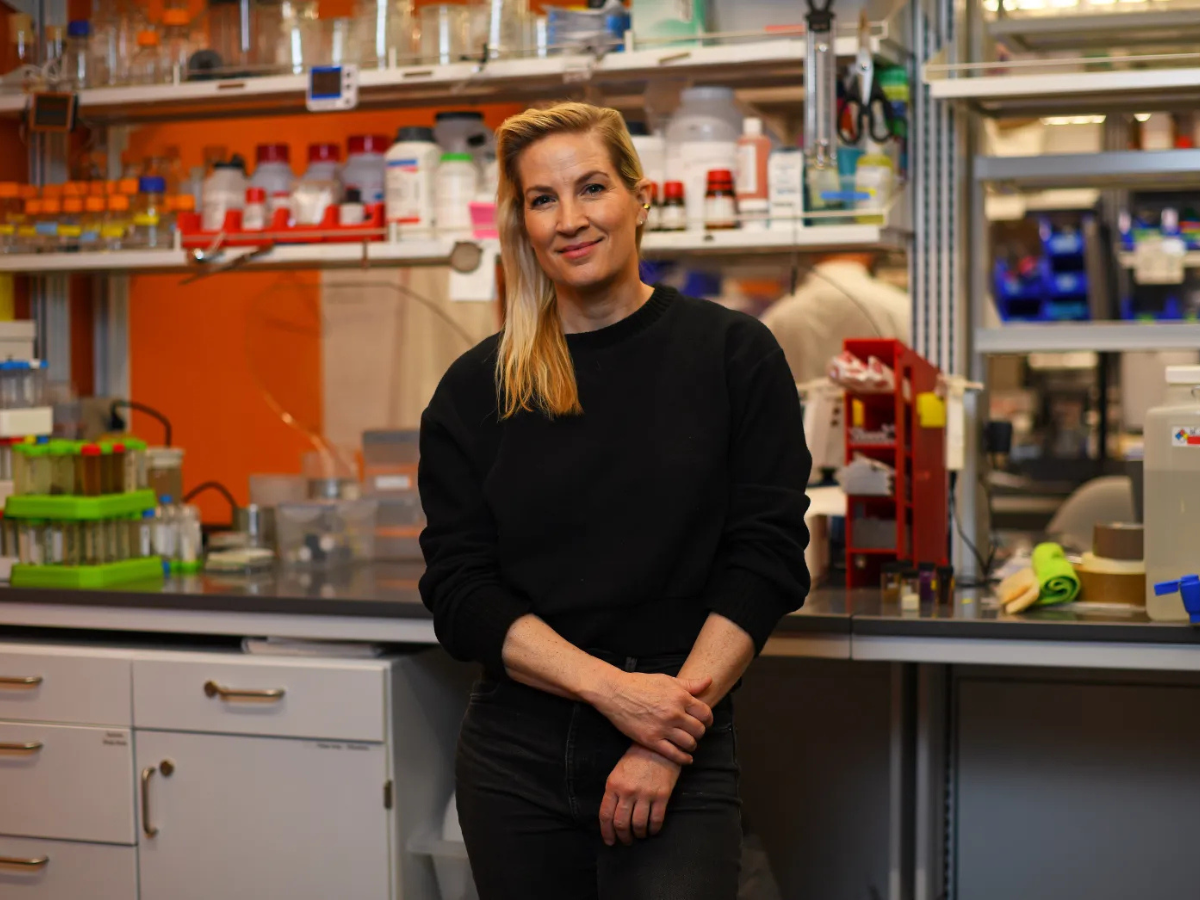

Nowadays, they meet in person at the Bakar BioEnginuity Hub, the recently completed lab and office space that is emblematic of UC Berkeley’s efforts to support bioscience startups. It’s part of a web of startup activity on campus that’s so vast, the university created a website to help people navigate it. Glyphic’s office, like many others in the building, is painted in bright colors and sits behind a pane of glass, where employees can be seen bent over their work benches.

Yang, CEO, and Estandian, CTO, both have degrees from Berkeley: Yang a master’s in engineering in translational medicine, and Estandian a bachelor’s in molecular biology. But that wasn’t their deciding factor in joining a Berkeley-based lab. Ultimately, it came down to space.

“If you’re in Boston, you literally are unable to get a lab space in the city,” Yang said. “Even if you do get a space at one of these incubators, you only get one desk and one bench.” When the fledgling company was offered free lab space at Lab Central, a popular incubator in Boston, they declined. They opted to pay for market-rate space at Bakar labs, which allowed them to grow their company to its current size, 13 employees total, with an additional 10 in the pipeline.

The university debuted the Bakar center late last year after converting a 94,000-square-foot Brutalist building that formerly housed an art museum. The funding for the renovations came from the Gerson Bakar Foundation, according to public 990 filings.

But generous lab space and access to cost-prohibitive equipment is only one benefit of joining Berkeley’s sprawling network for life sciences.

In early 2020, the university welcomed Richard Lyons as its first chief innovation and entrepreneurship officer. Lyons is responsible for several campus initiatives that benefit bioscience companies, among them the famous Skydeck accelerator.

More recently, Lyons started the Robinson Life Science, Business, and Entrepreneurship Program, an undergraduate dual degree program between the Haas School of Business and the Department of Molecular and Cell Biology in the College of Letters and Science. The program welcomed its first students in the fall of 2020.

This initiative grew out of a $10 million donation from Mark and Stephanie Robinson. The funds also went to the development of the Life Sciences Entrepreneurship Center, announced in early 2021 to serve as a place where early career scientists can receive resources and assistance in company formation. Professor David Kirn and his wife Kristin Ahlquist also donated to help create the center.

The goal, in part, was to join entrepreneurship and science in young minds. Lyons and his team saw that students were flocking to classes on biotechnology, and others were pursuing double majors on their own.

“When you code science and business in an 18-, 19-, 20-year-old’s brain at the same time, it’s not like two fields. It’s really integrated. They genuinely think of this stuff as integrated,” he said.

Berkeley was in a special position to provide the program, because of its undergraduate business and science curriculum, degree pathways that are difficult to combine at many schools.

“If you look at great, great business schools — Harvard is a great business school, Chicago is a great business school, Columbia, Stanford — they don’t have undergraduate business schools,” he said. “They can’t do this. We have great science and a great undergraduate business school. That’s unique.”

UC Berkeley benefits from the California Institute for Quantitative BioSciences, or QB3, a program created two decades ago to serve Berkeley and UCSF and UC Santa Cruz to commercialize research specifically in the life sciences.

“If you look at the whole pipeline, from discovery through to getting products in the market to help people, what is probably the weakest link, what they think of as a no man’s land, is when somebody leaves university and tries to start their company,” said Regis Kelly, director of both QB3 and the Bakar center.

QB3 offers infrastructure for startups, from providing mentorship, hosting seminars, and connecting founders with VC investors, who are ever-present at Bakar Labs. The program seeks to take research and commercialize it, translating it either into its own company, or selling off intellectual property to a larger company.

Today, as pharmaceutical companies have slowed down their R&D operations and opted for acquiring smaller companies in its place, universities have an opportunity to fill that gap.

“The importance of trying to stimulate startups and get new companies starting is probably the most effective way to get big drugs in the country,” Kelly said. He cites Eroom’s law, which states that despite our technological progress, drug discoveries are on the decline.