GigaCrop’s Chris Eiben wants to improve photosynthesis. Here’s how he’s doing it.

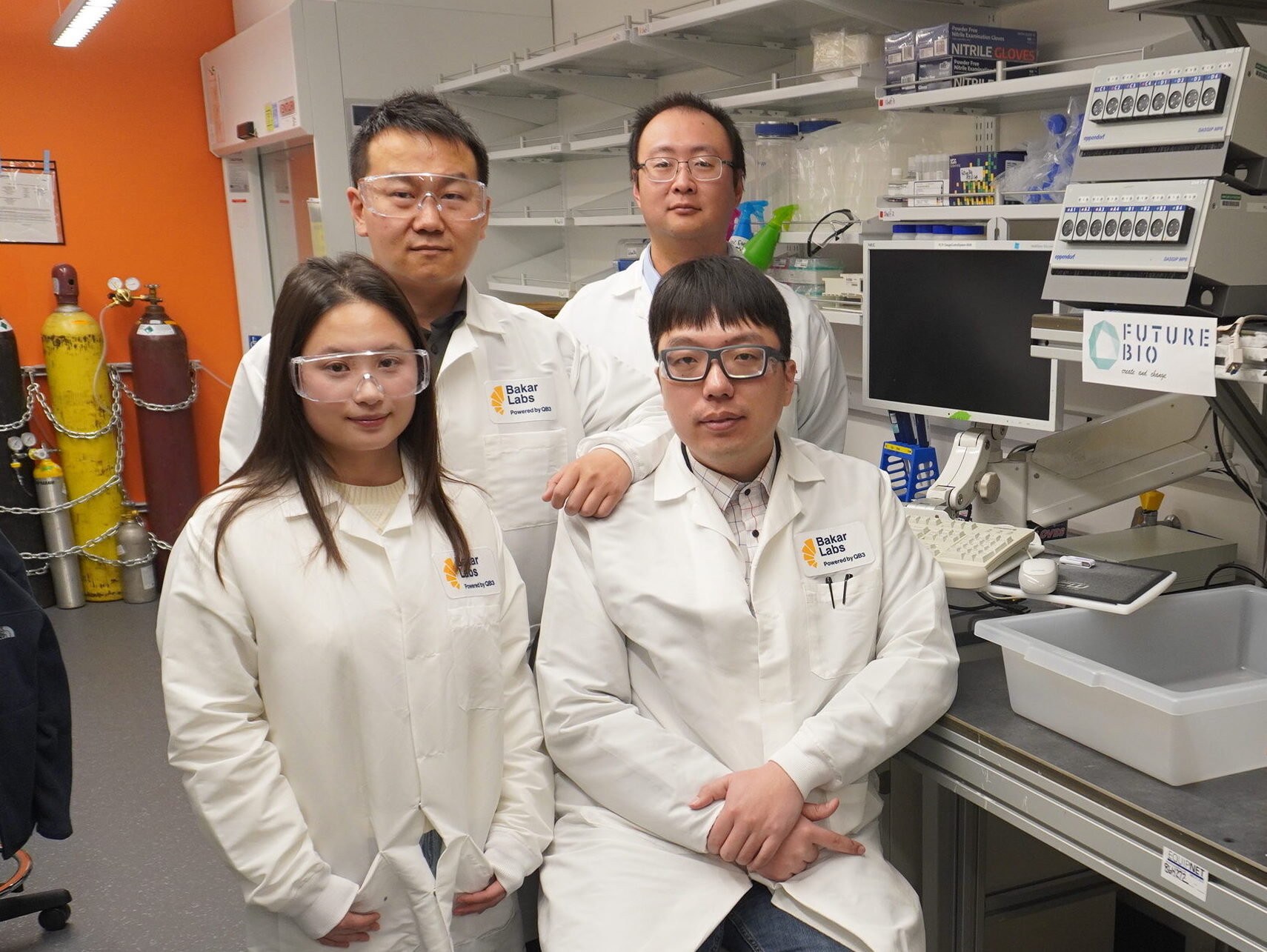

A Bakar Bio Labs Tenant Spotlight by Bella Liu.

“Civilization has a problem,” says GigaCrop CEO Chris Eiben. “We can’t make more land. Which sounds like a dumb comment, until you find out we’ve already used half the world’s land for agriculture. And the other half has things we like on it, like forests preserving biodiversity. In the future, there’s going to be more demands on land. We’ll need land to store carbon, and we’ll need more land to produce biofuels and bioproducts to help decarbonize difficult industries.”

“So the question is,” Eiben continues, “how do we do all that if we can’t make more land?”

The answer, in his mind, “is to make the land that we do use much more productive.”

Eiben and the rest of his team at GigaCrop, a Bakar Bio Labs tenant company, believe the key to doing so lies within plants. By making photosynthesis more efficient, Eiben believes that GigaCrop can improve plant productivity and, ultimately, increase crop yields.

“The thing holding plants back today is the enzyme Rubisco,” Eiben says. “It’s the first enzyme a plant uses to take CO2 and start turning it into a sugar. But the enzyme is slow, and it has a tendency to use oxygen instead of CO2. Which is incredibly costly for the plant to fix. I don’t have a clever way to make Rubisco better; land plants have been trying to improve it for 450 million years, which is a long time. Doing better than that is tough.”

So GigaCrop is inserting a parallel photosynthesis pathway into plants. “If a plant were an airplane, what we are doing is installing a more efficient engine. The trick is we have to do it while the airplane is flying. Plants must have a working engine at all times” he says. “Rubisco is part of a larger cycle called the Calvin-Benson cycle. Our pathway can exist next to the Calvin-Benson cycle, and they can both operate. But the plants will benefit because our pathway is faster and more energy efficient.”

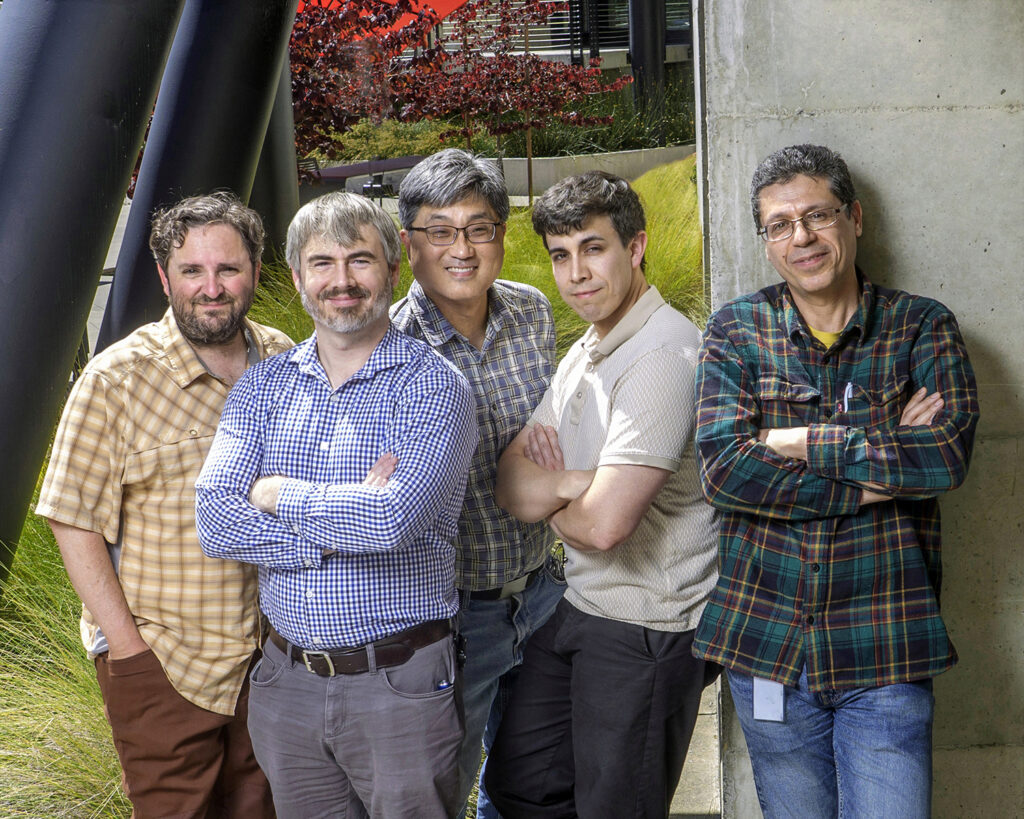

Eiben speaks highly of Playground Global, the lead investor in GigaCrop’s last round. He even notes that, after closing a round of funding last summer, it was Playground who suggested that GigaCrop (formerly known as Perlumi) rebrand so as to attract even more investors ahead of the next round.

“I have a heavy science background, so their business perspective has been great to learn from, ” Eiben says. “When I first started, I was like, I want a [company] name that’s neutral, that means nothing. But then the investors rightly pointed out, ‘If I was at a conference, and I had 200 different startups to talk to and I saw Perlumi, I wouldn’t know if it’s healthcare, I wouldn’t know if it’s software. I wouldn’t know anything.’ So they were like, ‘See if you can come up with something better.’”

Eiben adds that the resources and network connections afforded by Bakar Bio Labs have also been invaluable in helping him navigate the foreign world of business as a fish out of science waters.

“Being a founder is hard,” Eiben says. “Let’s say you need, like, an accounting firm. And you’re like, ‘I know they’re out there. But there’s a gazillion firms. How am I gonna find one that’s a good fit and understands startups and doesn’t want, like, $10,000 every month?’ One of the big advantages of being around other startup founders is that at lunch, for example, someone will come up and say, ‘Hey, how’re you doing?’ And you can be like, ‘I’m 12 interviews into this accounting thing and they are all terrible.’ And they’re like, ‘Oh, you should just use my guy.’ And then the problem is solved.”

“A lot of times, just being around other founders when you happen to be venting will create solutions. And then venting about something will generate the answer,” Eiben continues.

Ultimately, Eiben hopes to first implement GigaCrop’s breakthroughs in “major” crops like corn and soy, but said that they also have their sights set on eventually improving other mainstream plants.

“From my perspective, if you look back and say, ‘Why is it better to live now than 10,000 years ago?,’ there’s really only two places where improvements have come from: the technology is better and, arguably, we’ve decided to treat each other better,” Eiben says. “Now, I don’t know how to make people be nicer. The world’s complicated. But technological development, if done well, if done right, is one of these great fountains of abundance. If we can drastically improve how productive plants are, then we can use plants for bio manufacturing. We can have a new source —a sustainable, endless source — of fuels, of plastics, of materials.”

“I really do believe,” he says, “that with the right technologies, with the right developments, you can have a future that’s plentiful and abundant for everybody.”