Berkeley startup wins government award to develop radiation and lead poisoning treatment

From the story by Noah Haggerty in The Los Angeles Times

(Associated Press)

Whether its lead from old buildings, arsenic from contaminated food or strontium fallout from a nuclear explosion, heavy metals that enter the body pose a serious health threat.

With chemical properties exceedingly similar to typical nutrients like iron and calcium, toxic metals look virtually the same to the body. So, it starts incorporating the toxic elements into the skeleton, liver and brain.

Saving a patient requires removing the sparse toxic metals from the body with more than surgical precision, while leaving the abundant life-sustaining nutrients intact.

For many toxic elements, doctors have few options.

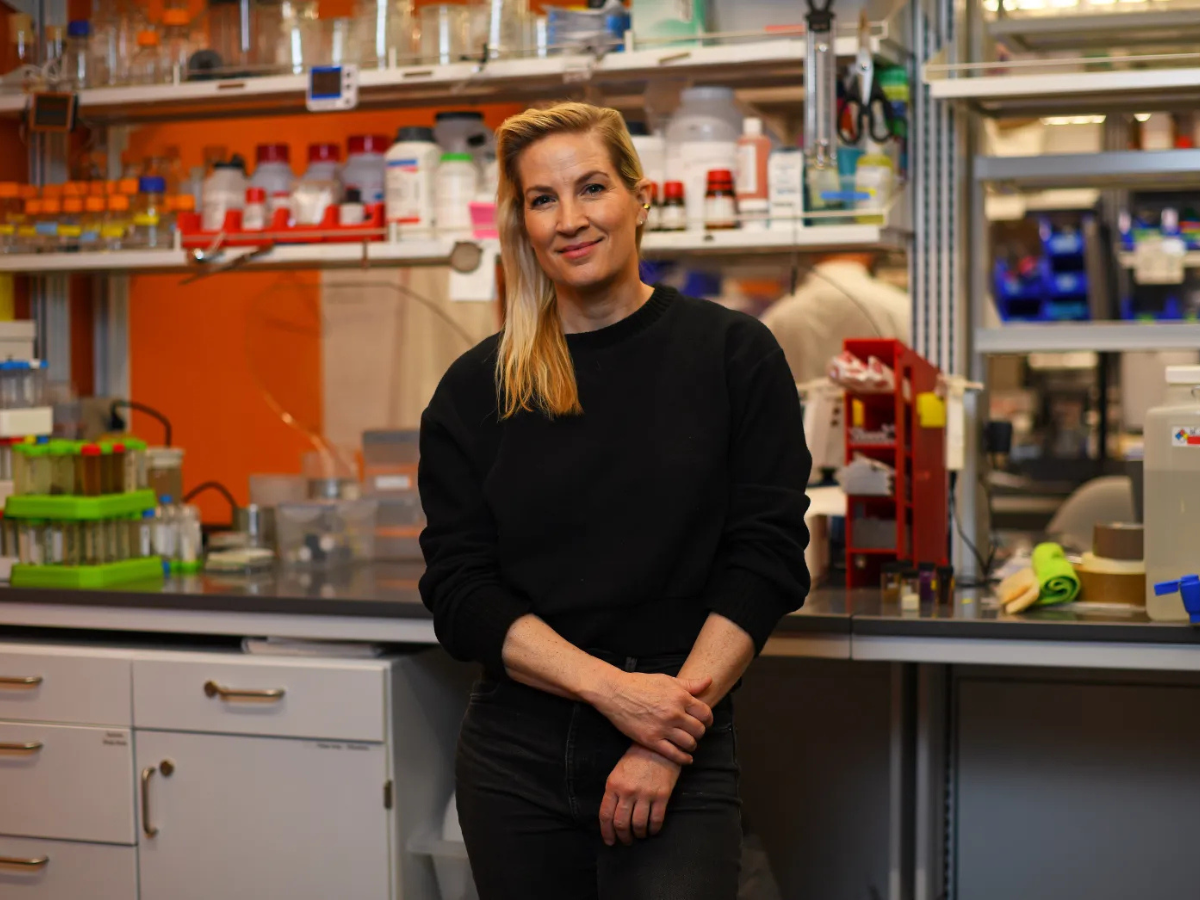

Now, a startup spun out of UC Berkeley and the Department of Energy’s Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory hopes to change that.

Recently, HOPO Therapeutics won a nearly $10-million initial contract from the Biomedical Advanced Research and Development Authority of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. The research authority is tasked with developing defenses against major public health threats, such as a pandemic or a chemical weapons attack.

“This is a priority for [the authority] — the development of new products that can be used to address these types of threats,” said Julian Rees, chief executive of HOPO Therapeutics, who started working on the drug at Berkeley Lab. “So, it’s been really exciting for us to partner with BARDA.”

Since BARDA was created by Congress in 2006, it’s supported 61 drugs through the Food and Drug Administration’s approval process. The authority also played an essential role in Operation Warp Speed to develop the COVID-19 vaccine.

HOPO Therapeutics’ drugs are designed to chemically bond with toxic metals only. By bonding, the medicine transforms the reactive metals into benign molecules that have little interest in interacting with different compounds in the body. The body can then easily excrete the metals.

Currently, few of these types of drugs — called chelators, derived from the Greek word for claw — are approved by the FDA. Those select few that have been approved have a hard time distinguishing between toxic metals and essential nutrients.

“HOPO chelators are extremely promising in that regard,” said Justin Wilson, a biochemistry professor at UC Santa Barbara who studies chelators and was not involved in HOPO Therapeutics work. “What the data show is that they have a very high selectivity for radioactive elements” over essential metals like zinc and calcium.

The HOPO chelators could potentially fill a crucial gap in lead poisoning treatment.

While the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention says a concentration of 3.5 micrograms of lead for every deciliter of blood constitutes lead poisoning, it doesn’t recommend treatment to remove lead until the concentration reaches over 45 micrograms, because of the adverse effects of existing treatments.

“So, there’s this huge window of people — primarily children — who have lead poisoning, but there’s no treatment available,” Rees said.

Lead poisoning can result in brain function impairment, fatigue, weight loss, paralysis and even death. It disproportionately affects children, whose bodies seek extra calcium — which lead can be mistaken as — to build bones.

Current chelators designed to treat lead poisoning can also remove essential metals such as calcium and zinc. If the concentration of lead is too low, the drugs would remove too much natural metal before putting a sizable dent in the amount of lead in the body.

Treating radiation poisoning is harder. Lead is a single element, but there’s a whole suite of elements with radioactive forms.

For radioactive elements, “there’s no real common denominator. … They belong to all different kinds of chemical families,” said Ira Helfand, past president of the International Physicians for the Prevention of Nuclear War.

“People who are exposed to these … are in big trouble and are liable to radiation sickness, liable to cancer down the road if they survive post-exposure.”

In a complex and messy real-world nuclear or radioactive disaster, Helfand said, HOPO’s medicine could serve only as a small part of the armor against radiation.

Much of the harm inflicted on victims of a nuclear strike — or nuclear plant catastrophe — comes from high-velocity radiation particles that pierce the body, damaging cells and their DNA. Only a small fraction of the injuries come from heavy metals that emit radiation from within the body.

And even then, some of the most abundant radioactive metals in nuclear fallout are particularly good at mimicking nutrients in the body, making it too difficult for the HOPO chelators to isolate them.

Instead, HOPO’s drug, which can target uranium and plutonium — elements found in nuclear weapons before they detonate — is better equipped to protect bomb makers, nuclear plant operators and victims of “dirty bombs,” conventional explosions that scatter radioactive material to harm bystanders.

Although state-of-the-art chelators approved by the FDA often need to be injected via an IV, HOPO drugs could be taken orally.

“If you think about the setting in which you want to apply this — where would you be getting exposed to radioactive elements? Typically some emergency situation,” Wilson said. “Having something on the field where you can take this as a pill very rapidly I think is a really big advantage.”

HOPO Therapeutics said the initial contract could be extended to more than $226 million, should development go well. The next steps for the company include demonstrating that the drug could be easily manufactured in large quantities — not just small samples for the lab — and human trials to study potential negative side effects.

The company’s ultimate goal is FDA approval.