At Minutia, Katy Digovich Is Tackling Diabetes Cell by Cell

From the story by Ron Leuty at the San Francisco Business Times.

Katy Digovich tried to get as far away from Type 1 diabetes as possible — literally and figuratively.

After graduating from Princeton University, she packed her bags and headed with friends to Botswana, where they started a social enterprise company leveraged cell phone technology to identify new sub-Saharan outbreaks of malaria, HIV and tuberculosis.

But while continuing to work in Africa with the Clinton Health Access Initiative, she learned she couldn’t get far enough away. People were surprised when they learned that the nearly 6-foot-tall, athletic-looking Digovich — a former basketball player in college — was living with Type 1 diabetes, a diagnosis in Africa that often translates into stunted growth, amputation and high mortality.

“Ultimately, I got really angry and the switch flipped. If I was born there, I would be dead. That really hit close to home,” she said. “I took stock of my career and threw myself into the diabetes space.”

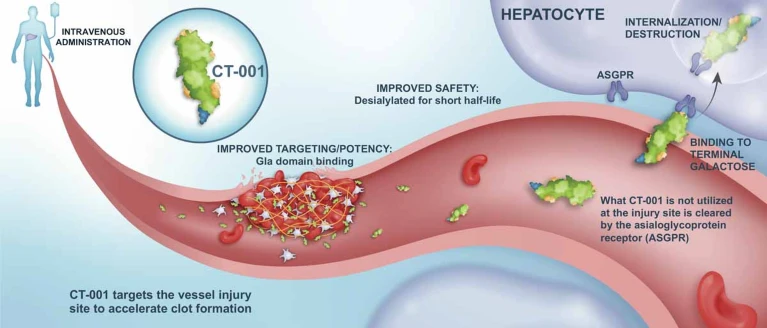

Digovich’s company, Minutia Inc., now is working to make beta cells that not only secrete insulin but also know when not to produce insulin when there already are high levels of glucose. An outpatient procedure delivered just below the skin into a Type 1 diabetes patient’s forearm would be a game-changer, since those patients today rely on continuous glucose monitors and manual injections or pumps.

But what spotlights Minutia’s unique approach is what it’s loading into the cells: dozens of golden, star-shaped nanosensors that sense different variables to monitor the health of the transplanted cells.

It is an advance, backed recently by a grant from California regenerative medicine funding agency CIRM, that could personalize and simplify care. Now Digovich and her team are trying to bring it home.

What’s the most exciting thing about Minutia’s CIRM-funded project? A lot of the work we’ve done to date has been with research-grade cell lines, and with CIRM, we are going to be doing this work with a clinically relevant cell line. They’re requiring us to do that, which I love, because I think the CIRM folks are very focused on giving funding that’s really trying to move you toward a product. As someone who sees myself as a transplant recipient, using research grade lines can be almost a little bittersweet — like, let’s start optimizing with a line that actually can become the foundation for a product.

With the nanosensors, these cells can monitored real time to make sure they’re surviving and basically not getting stressed out, right? One of the big things we’re excited about monitoring is inflammation and immune assault (where the immune system launches an attack on healthy cells), because we’re trying to move away from immunosuppression. We’re trying to create the type of transplant with the type of procedure that I want to receive, and systematic immunosuppression is not an option for me.

When people say “cell therapy” today, thoughts go to cancer and manufacturing cells for each individual patient. But you’re going toward an off-the-shelf allogeneic product. How does that change the game for patients? I’m really passionate about building things that I think would be a value that I would want to perceive. This is where I think there’s a link with my background in playwriting and the theater — imagining the future — but in a very personalized way. I’m writing a narrative of what I hope to have exist. In short, it’s access and affordability. This is anchored in experiences I had working in the countries I was working in with the Clinton Health Access Initiative, thinking of a transplant that actually could be delivered in those countries.

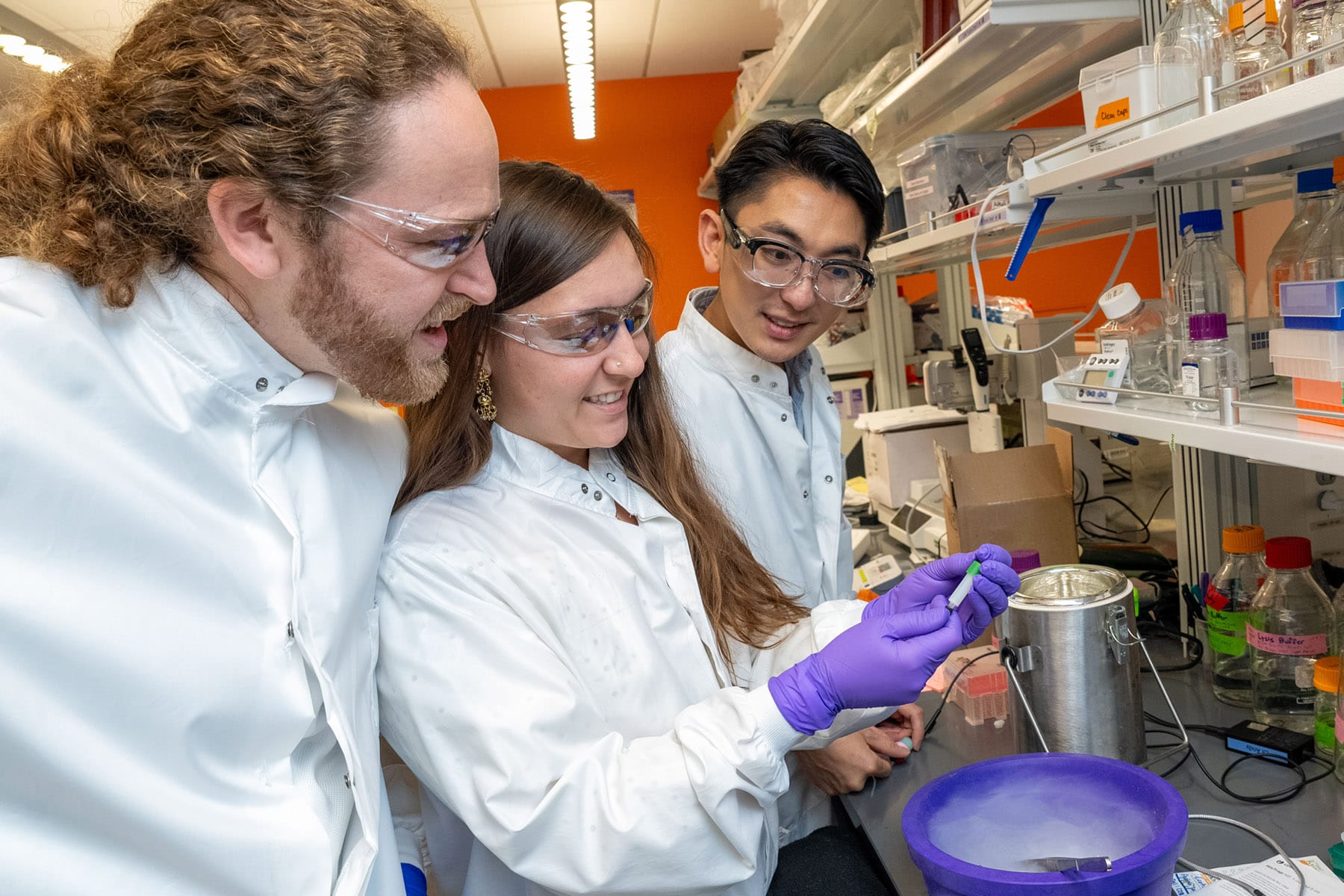

What’s Minutia’s biggest challenge at this point? Scaling up of manufacturing is a big challenge. Migrating to clinically relevant cell lines — different cell lines behave very differently. Beginning to de-risk some of the elements of how to store and ship is very pragmatic. We’re hoping to bring on our first full-time clinical hire — that’s a challenge we’re in the midst of solving.

How did the Clinton Health Access Initiative shape what you’re trying to do with Minutia? The access and affordability. Some of the big investors and some of the very close advisors of Minutia I actually met while I was in transit or in the airport for CHAI. My old boss there introduced me to co-founder Tuan Vo-Dinh.

So are you on a first-name basis with the Clintons? No, I am not. That would be amazing, but no.

There’s the oft-cited quote: “Be the change you want to see in the world.” What do you want to see in the world? We cover 100% of people’s health insurance and 100% of their dependents. This is something that’s deeply personal to me. The fact that I have had periods in my life where based on my family’s financial situation, insulin affordability was a problem, deeply impacts me. When you’re working in biotech, when you’re working in the cutting-edge space of health care, you should not be dealing with ridiculous co-pays for your child to get access to some medicine that’s important for them.

ABOUT DIGOVICH

• Age: 38

• Birthplace: Düsseldorf, Germany

• Residence: Oakland

• Education: Bachelor’s degree in biology, Princeton University

• Resume: Five years with the Clinton Health Access Initiative, with two years as head of special projects R&D; co-founder and managing director of Positive Innovation for the Next Generation, a social enterprise in Botswana focused on malaria, HIV and tuberculosis diagnostics

• Fun fact: 67 games for Princeton’s women’s basketball team, Ivy League all-rookie team in 2004. Also received a certificate in theater and dance from Princeton. I did a lot of improv — you get thrown curveballs and you accept them and go with it. And also written 17 one- or two-act plays.

• Favorite basketball player: I was a big, big Kevin Garnett fan. I’m also a big Bill Bradley fan.

• Favorite movie: I love zombie movies. Zombies are pretty predictable, but there are curveballs about humanity and viruses. I like “28 Days Later” — the soundtrack is really amazing — and “City of God.”

• First job: Waitress at Cafe Borrone in Menlo Park, a meeting hotspot for venture capitalists.

• Last book read: Rereading Gabriel García Márquez’s “One Hundred Years of Solitude.” I read it when I was working in Botswana. It’s probably only the second book I’ve reread in my life, along with “The White Boy Shuffle.”

• What can’t you do without: Insulin. I also am a coffee person — I stopped drinking coffee when I was pregnant and I’m just easing back into it.

ABOUT MINUTIA

• Founded: 2020

• Founders: Digovich, Matthias Hebrok and Tuan Vo-Dinh

• Headquarters: Bakar BioEnginuity Hub on the University of California, Berkeley, campus

• Employees: 11, eight full-time and three interns

• Funding: Raised $3.2 million and California’s regenerative medicine funding agency, CIRM, in August approved a nearly $1.2 million grant to the company.

• What it does: Packing engineered human stem cell-derived beta cell organoids — three-dimensional tissue cultures that can replicate much of an organ’s complexity — with nanosensors that can tell if the cells are accepted or getting stressed out after they are transplanted to produce insulin for type 1 diabetes patients.The sensors are 60-80 nanometers — a strand of hair is 80,000 to 100,000 nanometers wide.

• Why “Minutia”? It’s a word that always resonated with me. I had a teammate at Princeton who always shouted out, “We’re all minutiae” as a joke. But when it comes to success or failure of these transplants, it boils down to the little details that seem insignificant at first.